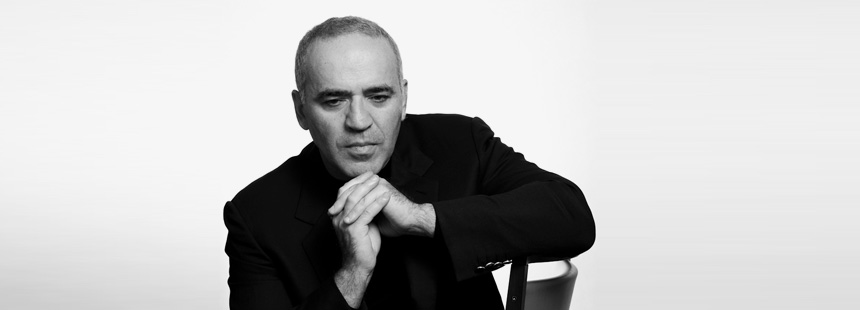

Taking a historical perspective, opposition leader Garry Kasparov explains why the Kremlin’s insistence that Russia’s ruling elite is in no danger of ever falling apart is entirely in vain.

The Implacable Logic of the Vortex of History

By Garry Kasparov

January 15, 2013

Kasparov.ru

In their endless quest to convince the conscious portion of the Russian protest movement that the Putin regime is here to stay, the Kremlin’s hack writers have switched from harping on the genetic inability of the Russian people to live in a democracy to attempting to “logically” explain the futility of hoping for a split within the ruling elite. However, their impassioned insistence that the elite is so monolithic is not backed up by historical analysis, and, moreover, is far too superficial.”

Historically, there is a certain point during the development of any society when the ruling elite works effectively for the beneficiaries of the existing system. Regardless of their social diversity, elite groups are all typically interested in preserving their existing privileges, and the desire to keep them often surpasses growing public sentiments to the contrary.

However, there comes a time when a split within the elite becomes inevitable. This happens first and foremost because of the growing inadequacy of the ruling authorities, which, owing to certain historical (or sometimes just personal) reasons cease to maintain the necessary balance between various elite groups. In England in 1640 and France in 1789, it was the members of the ruling elite who no longer tolerated monarchical tyranny who formed the driving force of those revolutions.

Moreover, the concept of the “elite” needs to be understood as something broader than a few dozen or hundred “noble” families of senior government officials. In any state pyramid, the federal elite relies on its own “clientele,” branches of elite groups from regional bureaucracies. The capital establishment – the aristocracy, bureaucracy, high-ranking officers, etc. – always reacts very clearly to ripples in its social fabric.

And the excessive inadequacy of the feudal powers can cause an extremely rapid turn of events. Because unlike in a democratic society, changes in the balance of power do not follow clearly-defined legislative procedures.

But while the ideological leaders of the English and French revolutions of the 17th and 18th centuries had relied on pre-existing public awareness or society’s readiness to stand up for its rights, neither Alexander Guchkov nor Vasily Shulgin could have imagined on the eve of the February Revolution in 1917 that they would soon see the abdication of Nicholas II.

If we consider the old inter-elite conflicts in governments that lacked monarchical legitimacy, then it becomes obvious that at some point the battle for power (and in the end, survival) inevitably requires the political (and in totalitarian states, usually also physical) destruction of yesterday’s comrades-in-arms.

The members of the post-Lenin Politburo had similar revolutionary origins, but the survival of the Bolshevik regime was dictated by the conflict that led to Stalin’s dictatorship and the destruction of almost all of Lenin’s so-called vanguard.

But in the post-Stalin era, Khrushchev and Georgy Malenkov’s speedy destruction of Beria and his apparatus was the party elite’s only reaction, its own way of fulfilling the social demands of the top Nomenklatura that did not want to live in fear of further midnight arrests.

The further divisions between those who supported Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization and those who favored Malenkov & Co.’s support of the status quo were also a result of many communist bureaucrats’ obvious attempts to distance themselves from Stalin’s legacy. But Khrushchev’s excessive zeal and capriciousness eventually got to the orthodox party functionaries, and they sent him into retirement with a carefully-planned conspiracy.

It is also clear that the fantastic state of the oligarchs of the Putin and Yeltsin eras share common roots. But this fact has nothing to do with the conflict brewing within the ruling elite. I repeat: the elites will always be united at a certain point when power is being established, especially power that lacks either monarchical or democratic legitimacy.

We cannot forget that the foundation of the Yeltsin-Putin regime was formed as a result of the attack on parliament in October 1993. Some may object that the parliament was reactionary. But that is beside the point, which involves how goals are reached, gross violations of the balance of power within a government, and the choice of an authoritarian model of government. This awful mistake became very apparent during the years of rule by the “man with the gun” from the shadows of St. Petersburg.

The union between the siloviki and the systemic liberals is actually a long-established union between various social groups that form the basis of the regime. This union was formed 20 years ago, in October 1993, when Alexander Korzhakov, Mikhail Barsukov and Pavel Grachev became siloviki. During the dramatic 1996 showdown in the Yeltsin circle, the systemic liberals succeeded in defeating their dangerous competitors, who were advocating for the abolition of presidential elections. The falsified election results in favor of Yeltsin were justified as “a necessary price in the battle against the communist evil.”

However, it quickly became clear that the systemic liberals would not be able to keep the situation under control by themselves. After the August 1998 default, the search began for the “correct” presidential successor, which was motivated by the serious threat posed by Yevgeny Primakov and Yuri Luzhkov’s possible rise to power to both the systemic liberals on the whole and to the Yeltsin family in particular. Putin was eventually chosen in this peculiar casting call. In addition to his origins in the security services, he had a leg up from his work in St. Petersburg as part of Anatoly Sobchak’s close circle.

With Putin’s hold on power, the siloviki have slowly but surely overshot the mark. Nevertheless, for the time being, their union with the systemic liberals provided a balance that defended the system from abrupt changes, since the overwhelming majority was interested in preserving the status quo. The Yukos crisis that began in 2003 became Khodorkovsky’s approximate punishment for his attempt to get out of the cash pool and start a new life according to civilized rules.

Let me remind you that the Yukos crisis ended not only with the criminal persecution of its managers and head employees, but also with the seizure of property, which would not have been possible without the direct cooperation of then-Finance Minister Aleksei Kudrin and other prominent systemic liberal economists. It was precisely with their help that the shell company Baikal-Finanzgruppe could on December 19, 2004, “win at auction” and instantly absorb the backbone of Yukos – the multibillion-dollar Yuganskneftegaz.

In this union with the siloviki, the systemic liberals fulfilled several important functions. First of all, they professionally aided the seizure of companies, flawlessly carved up the budget, and, most of all, legitimized the regime in the West, including by safely placing capital of the ruling elite in civilized countries. Secondly, they were faithful watchdogs for the political activity of the middle class that was emerging in the big cities.

But it was historically inevitability that a time came when these functions were no longer necessary. The newly-passed US Magnitsky Act and similar upcoming European sanctions are a painful blow to the safety of the foreign assets and property of the pillars of the regime. But meanwhile, in Russian cities, including among the systemic liberals’ numerous “clients,” the demands of the times are growing almost uncontrollably.

Thus, the typical system of balance was sharply disrupted. The systemic liberals can no longer cope with the role they have been assigned; their “holy” union with the siloviki as the backbone of the regime has exhausted itself. They are rapidly losing their position as junior partner in the ruling coalition and are transferring to the level of indentured bourgeois specialist. Within the existing system, the systemic liberals are deprived of any kind of historical perspective, since in the new configuration the regime has begun to rely on other forces – on the darkest and most backward segments of the population, on their most basic instincts.

That the Kremlin recently lashed back with its “anti-Magnitsky law” demonstrates its maximum severity and that nothing is off-limits, and it is a clear signal to the West that the regime’s style is no longer to use various sophisticated tricks, but to repress and frighten people domestically and use blackmail internationally.

The March Against Scoundrels on January 13 demonstrated that people understand perfectly well that there will not be any reforms while Putin is in power. It is obvious that the protest movement has sharply radicalized over the past year and is no longer persuaded by those who wish to “evolve” or “adapt.”

I have no doubt that the systemic liberals will be forced to change their behavior if threatened with destruction or defeat. As we still know from the Soviet classics, those who are drowning are left to save themselves. Bearing in mind the lessons of history, if their leaders do not have the strength to lead the middle class, they then will be forced, on the contrary, to seek its public support.

Translation by Kasparov.com.