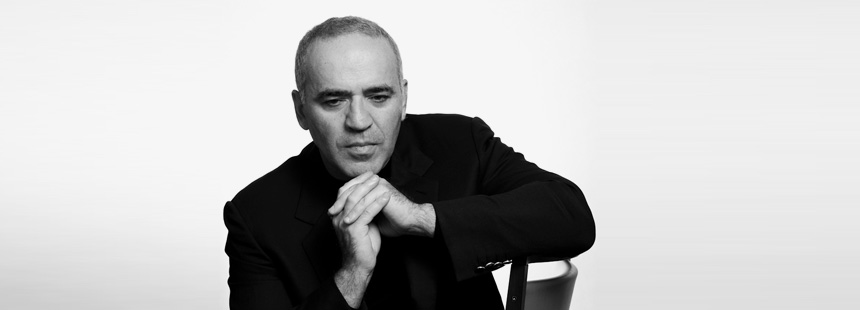

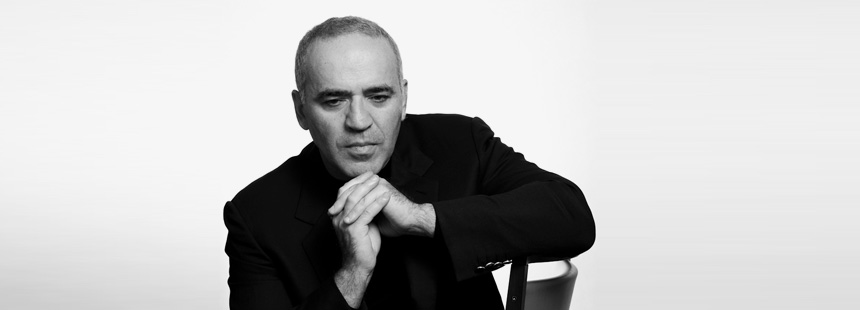

In recent years, it has become fashionable for publicists and academics alike to compare Vladimir Putin’s rule of Russia to Stalin’s rule of the Soviet Union. While parallels certainly do exist, the reality is much more subtle and complex. In his latest op-ed, opposition leader Garry Kasparov provides an insightful look at how Putin has adapted Stalin’s justice system into the monotonous conviction-spewing behemoth that it is today.

The Humanization of Stalinist Justice

By Garry Kasparov

July 24, 2012

Kasparov.ru

It seems to me that recent statements about how the atmosphere of the year 1937 is currently being actively revived in Russia do fully take into account the specifics of our times and the mentality of the Russian government, which is devoid of any sort of ideology. Sure, intimidating the population, which is made to live in a constant state of fear, is still the basis for the survival of any dictatorship, even a modernized one. But the changing world, where corrupt dictators invest money stolen from their own countries into the financial and material infrastructures of the same Western democracies that they hate so much, requires a new, more humane approach.

During the years of the Great Terror, Stalin’s judicial machine, driven by revolutionary expediency and headed by the tireless innovator Andrey Vyshinsky, who was atoning for the sins of his Menshevist youth in his post as Procurator General of the USSR, made a decisive break with such relics of bourgeois rights as the presumption of innocence. According to Vyshinsky, an arrestee’s own confession sufficiently constituted state’s evidence for a guilty verdict. And the ability of the NKVD’s executioner to elicit confessions is at least as good as his colleagues in the Gestapo. If the fantastical confessions that were knocked out under torture corresponded with reality even a little, the interrogation records from that era could provide the basis for quite a few detective and adventure novels. NKVD specialists were capable of squeeze out any confession, turning primitive preparations for acts of wrecking or sabotage into participation in the secret construction of a tunnel from London to Mumbai…

Today, Putin’s judicial system has taken the path of humanizing this creative “production process.” Nobody has officially annulled the principle of the presumption of innocence, and extracting confessions from suspects is no longer a systemic practice (although the tried and true methods of our forefathers, naturally, have not been forgotten). But the established Stalinist principle of “the agencies make no mistakes” has turned out to be exceptionally resilient. The percentage of acquittals, paradoxically enough, is much lower in contemporary Russia than during the late 1940s.

The main innovation of Putin’s judicial system is the near one hundred percent willingness of its judges to accept any assertion made by the prosecution on faith. In both criminal and administrative cases, the opinion of “a man in uniform” always outweighs any witness testimony or even video evidence presented by defense lawyers. Routine perjury by OMON riot police, which has resulted in numerous convictions of dissenting oppositionists, goes together naturally with the prosecutorial drivel that formed the basis for the harsh verdict in the Yukos case. And the case against Pussy Riot has shown that the fantasies of Putin’s prosecutors are swept up just as much in metaphysical heights as in geopolitical expanses. The indictment, which reeks of medieval ignorance, goes together logically with the arguments that the “blasphemers” need to be kept in extended detention, due to the “obvious” connection between their unholy activities and acts of terrorism against the Muslim clergy in Tatarstan.

In the near future, following the legislators who have fallen into a defensive rage, the highest judicial authority in Russia is going to have to come up with a theoretical basis for a new law enforcement policy. And Supreme Court Chairman Vyacheslav Lebedev, recently reassigned by Putin regardless of his elderly age, together with Constitutional Court Chairman Valery Zorkin, who is making every effort to atone for his “sin” of supporting the current constitution during the Autumn 1993 crisis, are both are fully prepared to justify the universal principle of Putin’s justice: “a man in uniform is always right.”

This rationalization allows for a sharp drop in the pointless amount of time spent in the courts, where identical judges with the same impassive facial expressions monotonously grind out the same convictions under the government’s dictation.

Translation by Kasparov.com.