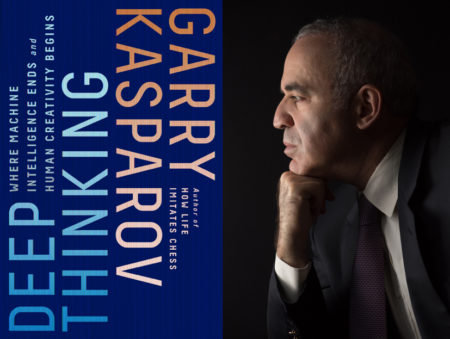

As a chess legend, Garry Kasparov always looks several moves ahead—and his new book envisions what the future will hold

Garry Kasparov is one of chess’s all-time great champions, a political activist, and a vital opponent of Russian President Vladimir Putin since giving up competitive chess in 2005. He remains a provocative thinker. Deep Thinking, co-authored with Mig Greengard, is his third book, a cerebral and stimulating exploration of artificial intelligence, work and the future, while plunging into his iconic chess matches with the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue. “Intelligent machines will continue that [mechanization] process, taking over the more menial aspects of cognition and elevating our mental lives towards creativity, curiosity, beauty, and joy. There are what truly makes us human,” Deep Thinking argues.

Garry Kasparov is one of chess’s all-time great champions, a political activist, and a vital opponent of Russian President Vladimir Putin since giving up competitive chess in 2005. He remains a provocative thinker. Deep Thinking, co-authored with Mig Greengard, is his third book, a cerebral and stimulating exploration of artificial intelligence, work and the future, while plunging into his iconic chess matches with the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue. “Intelligent machines will continue that [mechanization] process, taking over the more menial aspects of cognition and elevating our mental lives towards creativity, curiosity, beauty, and joy. There are what truly makes us human,” Deep Thinking argues.

During the build-up to his Vancouver TED Talk last week, Kasparov and I went in-depth on how Deep Thinking might challenge and surprise readers, including whether super-intelligent machines will turn on their creators. We also covered Stanley Kubrick, Vince Staples, George Orwell, Canada’s role in opposing Putinism, and why he thinks Donald Trump is a Marxist.

Q: Trump is the Republicans’ “chickens coming home to roost,” Bill Maher told me. What’s your response?

A: When you put party over principles, you can’t avoid tripping over your own hypocrisy and contradictions eventually. The GOP establishment refused to stand up to Trump during the primary because they wanted his voters in order to beat Hillary. Then he won the primary, and then the general, and the GOP both times decided it was better to cling to their grasp at power, to cling to Trump and all he stands for, a decision that should destroy the party or drag it down for a generation.

Q: What do you hope people might take away from Deep Thinking? What might challenge and/or surprise readers?

A: The overall message is that we must be optimistic about the future because it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. If we are creative and ambitious, intelligent machines will liberate us and be as profound a boon to our prosperity as electricity. If we are fearful, and fail to press ahead, we could be overwhelmed by automation and inequality. Deep Thinking puts AI and our hopes and fears into a practical context of centuries of our technology changing our lives and redefining what it means to be human, from labour to art.

Many readers will be surprised by how frequently the origins of psychology and computer science are connected to chess. This ancient board game has been considered a nexus of cognition going back to Alfred Binet, the co-creator of the IQ test, who was fascinated by chess masters. And luminaries like Alan Turing and Claude Shannon invested a great deal of time and effort on creating chess programs.

Another area of great public interest and importance is how intelligent machines are affecting education and our children’s minds. I’ve seen up close the benefits and drawbacks of kids working with super-strong chess programs in their training, and they definitely think differently than past generations thanks to this alien influence. While we are making our machines more intelligent, they are also changing how we think.

My participation in the decades-long experiment to create a world champion-level chess machine is the core of half the book, both as a sport and scientific quest and as a metaphor for humanity’s relationship with technology. I finally share my view of my two matches with the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue in detail.

Q: In the Canadian documentary Kasparov and the Machine, you alleged that IBM’s behaviour during the 1997 rematch with Deep Blue was emblematic of systemic, dodgy, Enronian corporate culture. Did this temper your faith in capitalism?

A: That’s an interesting thought. I think it was more a case of tempering my own Soviet-born naiveté regarding big corporations dedicated only to their own immediate interests—depending on the CEO and other directors, of course. It’s not as if every large corporation acts like Enron, or would if given the chance. I don’t equate IBM’s behaviour to Enron’s real crimes, of course. I only make the point that the idea that a big, successful American company might bend or break the rules was seen very differently after Enron. Nobody told me, “IBM would never do anything underhanded” after Enron.

I criticize IBM’s behaviour during the match, but was it wrong from their CEO’s perspective? From their shareholders’ perspectives? Probably not, and, as I say in the book, in retrospect it’s hard to blame them for not giving me a rematch, for example, although I’d like to. They said at the start the science experiment was over, that they wanted to win, and they got what they wanted.

I’m not in favour of a regulation-free world. I align myself with Teddy Roosevelt, who broke up the trusts. Regulation is necessary, but it should be in favour of the consumer, the citizen, and freedom.

World chess champion Garry Kasparov studies the board shortly before game two of the match against the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue (R). (Mike Segar/Reuters)

Q: I enjoyed Deep Thinking’s cerebral cultural references, like the discussion of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Stanley Kubrick said dismissively of New York critics: “New York was the only really hostile city. Perhaps there is a certain element of the lumpen literati that is so dogmatically atheist and materialist and Earth-bound that it finds the grandeur of space and the myriad mysteries of cosmic intelligence anathema.” Thoughts?

A: That’s very good; I hadn’t seen it. I cannot speak on the intellectual clans and dogmas of New York or America myself, but I like the rest of Kubrick’s sentiment. Many people think they are too refined, or too rational, to entertain a real sense of wonder in themselves or in others. This is preposterous to me, since the natural world is full of endless wonders, both on Earth and especially in space, no matter how you think it was created.

This is related to how many so-called pragmatists want nothing to do with space exploration or other kinds of ambitious endeavours that don’t have a clear payoff. This mentality is hugely damaging to our success as a civilization. Our desire to understand the universe is kindled by curiosity and wonder, and this has fuelled countless scientific breakthroughs.

Q: The rapper Vince Staples wrote on Twitter: “Get out of that ‘this is what a n—a can be’ box. Its 2017 the robots about to come we gotta move on.”

A: My Deep Thinking co-author Mig Greengard shared this with me at the time, clearly impressed. Honestly, I found the language a little confusing and I didn’t know who he was, which I suppose isn’t a surprise considering my musical tastes are quite conservative! But the thought I believe he is expressing is important, and represents a view some futurists have put forth: that constructs like race will decline in relevance in a roboticized world. That how well one human subset or community—a race, a nationality, a religion—is doing will be secondary to how well humanity in general is doing in face of the robot revolution.

A related vision is common in sci-fi, where the existence of aliens encourages humans to realize that they have nearly everything in common and are one people. Our skin, our borders, all seem petty compared to alien races and the scale of galaxies. Nobody in the Star Wars universe cares about white or black humans, it seems, and what meaning could physical appearance possibly have when there are sentient beings that look like lobsters or like Jabba the Hutt? Unfortunately, in the real world, such hopeful sentiments are regularly refuted by our stubborn insistence on always finding someone to discriminate against.

MORE: An interview with the Canadian godfather of deep learning AI

Q: In your book, you argue that intelligent machines will help us achieve more creativity, beauty, and joy. Is there anything else you hope the book accomplishes?

A: I hope it engages people into this debate in a positive way, against equally impractical tides of AI utopianism and dystopianism. People need to realize this is real, it’s happening, and what matters is how to make the best of it today, tomorrow, next week, and that is the best way to build a bright future. I’m glad experts are pondering the dangers and dreams of the distant future, of course. I’m on the executive board of the Foundation for Responsible Robotics, founded by the amazing Noel Sharkey, and I stay engaged on the moral and other implications of autonomous robots, et cetera. But I want to be a voice of reason, based on my personal experiences, and an interpreter of how all these incredible innovations might affect our day-to-day lives.

Q: Will super-intelligent machines surpass and turn on humans? You note in the book that corporate “R&D budgets have been slashed over the years as investors take a sceptical view of anything that doesn’t feed the bottom line.”

A: That machines will surpass us in intelligence is inevitable. What it means is unknowable. Will they be sentient? What will they care about in the sense that determines our human motivations? All the theorizing by the experts and non-experts makes for interesting conversations and dramatic headlines, but it’s more likely we will be surprised by how our technology develops and how it is used, as we so often are.

(AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

Q: Do you worry that those left behind by intelligent mechanization will vote for authoritarians like Donald Trump?

A: The political issue is more one of ignorance and populism than authoritarianism. If people are being left behind, impoverished economically or even culturally, they will always be easily targeted by demagogues of any stripe, exploiting their hate and fear and making impossible promises. That impoverishment is more likely if we fight a doomed battle against automation and new technology, when what those people need most is the ambitious new tech that is the only proven way to create sustainable industries and jobs.

Q: How about Trump calling the media “enemy of the people”?

A: It rang an alarm bell for me as it would for anyone who knows the dark history of this phrase, and its related “enemy of the state.” Lenin and Stalin enjoyed these phrases, a tactic to position their critics as threats to the nation itself. It’s a fundamentally undemocratic accusation, a threat against the right to protest and oppose the government.

Q: What’s your message to Republicans like Reince Priebus and Sean Hannity that are cheerleading Trump’s war on the press?

A: My message is that people will remember! Unfortunately, I’m not confident that’s true. Ratings are king and the money keeps flowing, and partisanship is so strong today that people rely on a few sources absolutely instead of thinking critically. So even being a cheerleader for a gameshow-host president with no respect for the rule of law or America’s reputation in the world may not be a career-ending move.

Q: How about your response to Canadian-American David Frum’s Atlantic story,Seven Lessons From Trump’s Syria Strike? Frumian conservatives like Anne Applebaum also believe Trump’s dangerous, authoritarian tendencies will be worsened by this.

A: Without getting into approving or disapproving of the Syria strike itself, it did represent a natural move from Trump, or any leader whose agenda is being thwarted. He sought out a path of rapid action that could not be blocked by Congress or a judge, despite contradicting everything he’s said in the past about American involvement in Syria and elsewhere. He likely did it simply to say, “Look, I can do things. I have power!” And yes, it’s dangerous that the strike got the approval he desperately seeks from the establishment despite having no basis at all in any strategy for the region or for American policy. It makes it harder for institutions to stand up to him.

In this photo provided by the U.S. Navy, the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Ross (DDG 71) departs Rota, Spain, on March 29, 2017. The United States fired a barrage of cruise missiles into Syria Thursday night in retaliation for a gruesome chemical weapons attack against civilians, the first direct American assault on the Syrian government and Donald Trump’s most dramatic military order since becoming president. (Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Robert S. Price/U.S. Navy via AP)

Q: I propose that Trump is a Marxist, as in Chico Marx’s line in Duck Soup: “Who are you going to believe, me or you own lying eyes?” He flagrantly contradicts things millions of people saw him say on TV, like that press conference where he called upon Russia to hack Hillary Clinton’s emails. Whatever happens with Washington’s investigations, there seems to be Republican amnesia about Trump’s most consistent position: his praise for Vladimir Putin.

A: Or like the line attributed to Groucho: “Those are my principles. If you don’t like them I have others!” Rhetoric matters, but at the end of the day policy matters more. Trump’s Russia issue isn’t going away, and the truth will out, as Shakespeare wrote. We have yet to see if Trump will defy Putin’s wishes in anything that really matters to Putin and his gang.

Russian President Vladimir Putin attends a meeting with French Senate President Gerard Larcher (not pictured) in the Kremlin on April 5, 2016 in Moscow, Russia. Larcher is on a visit for bilateral meetings with Russian leaders. Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images

Q: How long do you give Putin?

A: I have no idea how long Putin will last. The good news is, Putin doesn’t know either. It will be sudden and it won’t be peaceful. He has burned his bridges.

Q: How is Canada going on opposing Putinism?

A: Better than many other Western nations, although there is always more to be done, of course. The passage of a Canadian Magnitsky Act looks very likely now, after receiving tremendous support in the House of Commons. It’s vital to pressure Putin and his cronies like this, in ways that matter to them, not merely more diplomatic lip-service for public consumption.

Q: What do you think of Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s foreign minister?

A: I’ve known her for a long time, and it’s a truly remarkable occurrence for the right person to be in the right place like this. Her appointment reflected a surprising and welcome display of realism and backbone by Trudeau in foreign affairs, when I was afraid he would imitate Obama’s failed appeasement policies. Instead of praising her myself, you can take Freeland’s measure by how quickly and desperately her critics made themselves known. She has all the right enemies—the thugs and dictators and slanderers—and some enemies are worth having.

Q: What can we learn from chess to oppose Trumpism? The last time we spoke, you said: “One lesson is to not to play desperately if your position is worse but still reasonable. Lashing out wildly in an inferior position usually only hastens defeat. Meanwhile, solid, stubborn defense can demoralize the attacker, make him lose confidence. When that happens, the tables can turn. Keep fighting, stay steady, keep morale high—and public protests are good for all of these things.”

A: In several ways, this is what has happened in the last month. Trump has reversed himself on many major issues, from China and NATO to Syria. Trump was failing everywhere, and while he of course denies it, since people like him can never admit to failure or changing their minds, he has begun to defer more to establishment experts on foreign policy, and the same will probably happen domestically if resistance continues. He’ll take tactical retreats and superficial victories over public losses.

Q: You are the President of the Human Rights Foundation. Why hasn’t the rise of capitalism in China made China more democratic?

A: As Milton Friedman wrote, “History suggests that capitalism is a necessary condition for political freedom. Clearly it is not a sufficient condition.” Dictatorships can exist with free markets—not that China is really a free market—especially in poor countries where the regime insists that it’s a choice between food and liberty, a false choice. But increasing affluence will inevitably result in political pressure.

Another factor is how China, like Russia, like Saudi Arabia, can fund repression with the immense wealth it receives from the free world. There is little pressure on these regimes to reform when leaders can become rich and enjoy their riches abroad while ruling with absolute power at home.

Q: The great trade unionist Jimmy Reid once said: “The political spectrum is not linear but circular. In my experience the extreme left always ends up rubbing shoulders with the extreme right. They are philosophically blood brothers.” Are we seeing this in Julian Assange and Jill Stein sharing Donald Trump’s enthusiasm for Putin?

A: It comes down to power, not ideology, something George Orwell understood and described very well in one of my favourite books, Homage to Catalonia. Right, left, Greens, Baathists, whatever: it comes down to grabbing and holding power and using ideology—or religion, race—as a justification. The brilliant activist Iyad El-Baghdadi has explained with great lucidity regarding how Middle Eastern dictatorships use Islam for what is always a political end.

Q: The Trump administration has decided that the government’s Countering Violent Extremism program is no longer going to target anyone except Islamists. Wearing your strategic expert cap, how should governments counter white supremacists like Dylann Roof and Alexandre Bissonnette, and anti-government militiamen like Timothy McVeigh?

A: I wrote in Winter Is Coming that the growth of violent extremism is partly a consequence of how the developed world has become complacent and defensive about its own greatness and ambition. Why would a relatively affluent young man in Australia or Germany or the USA become a terrorist? Extremism yes, radical Islam, okay, white supremacy or whatever, but what is the bigger picture? What is creating such fertile ground for recruitment in the developed world? Young people, especially young men due to culture and perhaps testosterone, dream about changing the world, making an impact, doing big things. Now our young people are told life was better in the past, that we should be less ambitious and hold on to what we have. The grand narratives of exploration and change that drove the world forward for a century have been tamed.

So where do poor young people turn? ISIS has a mission for you to change the world! It’s a horrific vision, but it’s a vision. Perhaps for white supremacists, you can add the additional storyline that they believe that they are having something taken from them by outsiders, by immigrants. Not only are they losing out and bored, but they think they are victims and that they know who is responsible. But again, I prefer to look at the bigger picture. You’re always going to have dangerous, disaffected people in any society, and some will be violent. Increasing prosperity and reducing inequality won’t solve that completely. But having big, positive dreams and a society that makes it possible to achieve those dreams is what we must strive for.

Q: To regret is human. What’s your greatest regret?

A: Learning from our mistakes is critical for improving, but even I don’t have patience for ranking my regrets. Regret is a negative emotion that inhibits the optimism required to take on new challenges. You risk living in an alternative universe, where if only you had done this or that differently, things would be better. That’s a poor substitute for making your actual life better, or improving the lives of others. Regret briefly, analyze and understand, and then move on, improving the only life you have.

Alexander Bisley is a regular Maclean’s contributor. Elsewhere, his zeitgeisty political interviews include Howard Dean and Colson Whitehead.