Garry Kasparov: You cannot enter Europe with stolen property !

Last week was my first visit to Kiev since the victory of Maidan’s “Revolution of Dignity.” Discussions with various groups allowed me to better understand the mood and capture the changes that took place in Ukrainian society in the past year. The veneration of heroes of the Heavenly Hundred, deep respect for the state symbols of Ukraine, a growing generation of true patriots, which I saw when visiting one of Kiev’s schools – all point to a transition to a new level of national consciousness, which for citizens of the Russian Federation can understandably provoke envy. The ridiculous insistence of Russian state propaganda that Russophobic attitudes are growing in Ukrainian society is laughable – the most popular Ukrainian television show Shuster LIVE – is fully in Russian.

One can state with confidence: there is a nation being formed in Ukraine. This nation is well aware of its own interests and is ready to defend them. It is striving to determine its own fate, trying to avoid becoming a toy in the hands of local oligarchs or, even worse, a Kremlin dictator. And, of course, this nation is committed to the restoration of its territorial integrity: at almost all of the meetings I attended I was asked questions about the Crimea and the relationship of the Russian opposition to this problem.

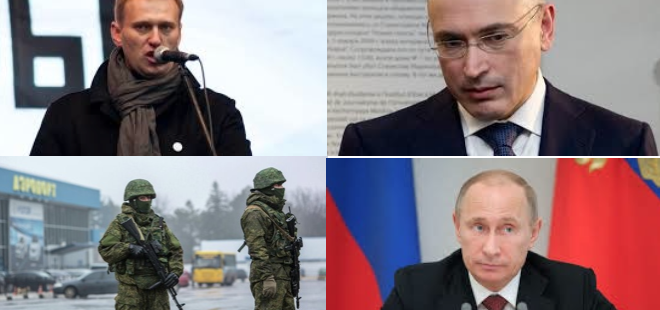

Alas, the position of many Russian opposition supporters who call themselves the “European choice of Russia” raises many doubts. The debate that followed statements of Khodorkovsky and Navalny on the “Crimea issue” was quickly silenced, and since then we have seen prominent representatives of civil society, one by one, repeat the position that was formulated by Navalny and Khodorkovsky: “However illegal the annexation of Crimea might have been, its return to Ukraine is not possible in the foreseeable future.”

By making such statements, they overlook that the question of ownership of the Crimea is not just a territorial dispute – it is a difficult and complex problem that affects a number of challenges of a more fundamental nature. I am afraid that many members of Russia’s opposition not only do not understand the nature of these challenges, but also do not see (or would prefer not to see) the fact of their existence.

The first of these challenges is the foreign policy one, which demands that post-Putin Russia adopt a global attitude in regard to its place in the world. The effects of Putin’s aggression will not go away by themselves with the disappearance of Putin – Russia’s new government will need to take drastic steps to change the situation. If that does not occur, the attitude of Ukraine, the Baltic countries and other neighbours, who perceive Russia as an aggressive and dangerous state, will continue for decades. This attitude may well suit those who deliberately portray Russia as a besieged fortress to cement their own power. However, for the leaders who seek true security and prosperity for Russia, they will need to change this dynamic – which is impossible without return of the Crimea to its rightful owner.

People who think that the Crimea problem will be resolved through the integration of post-Putin Russia into Europe, where borders are transparent and national sovereignty is somewhat of an outdated notion, are guilty of serious self-deception. Nobody will allow Russia to enter Europe with stolen property! Until the Russian Federation’s flagrant act of international gangsterism, which the capture of the Crimea truly is, is unequivocally denounced, there cannot be even a hint of discussion about admitting Russia into Europe.

The second challenge is of an internal political character and has to do with building a stable democracy in Russia. To justify their opposition to Crimea’s return to Ukraine, members of the Russian opposition are appealing, as a general rule, to “democratic principles.” They refer to the fact that the majority of Russian citizens are opposed to such a return, and argue that “democratic government” cannot go against the will of the people. However, this position is built on false notions of what constitutes democracy.

Democracy involves not just majority rule, but the rule of law. If majority rule is not subject to law and is not limited by it, then we have not a democracy, but ochlocracy – tyranny of the majority, which is not in any way more attractive than tyranny of the minority.

From these simple axioms a rather obvious conclusion can be derived: The question of whether Crimea should or should not be returned should not even be a question for the new government. If this new government allows itself to flout international law and approve the international crime committed by the Putin regime, it will at that very moment cease to be democratic. It will sink to the level of the existing regime, simply reproducing the system that has been put in place.

Furthermore, I would like to note that the argument of “the people will not favour this” seems to me untenable. The transformation from Putinism to a full democracy will only be possible and successful if, in the process, there comes to form a fundamentally different political and informational environment. Citizens must become aware of their personal responsibility for the international isolation of their country, which will in turn make a change in attitudes about the “Crimea issue” absolutely plausible.

It so happens that Crimea has become for Russia a kind of “poison pill.” Only recently it seemed that the removal of Putin from power would, in a relatively short time frame, allow for the necessary institutional changes that would pave the way for a so-called democratic transition. Now, however, the professed willingness of many opponents of Putin’s regime to build a post-Putin Russia on the foundation of a cynical denial of international law raises serious questions about this. If such a transition were to take place, the new Russian state system would be essentially no different from the present one.

Against this background, the arguments of many in the “opposition” about the benefits of doing “small things” and the importance of participation in the elections looks rather silly. There is a fascist, personalistic dictatorship in power in Russia, and it has unleashed repression (still surgical?) against its opponents in the country and now has seized territory beyond its borders. Dealing with it by electing several opposition deputies to a District Council is as effective as taking vitamins for gangrene.

It is worth noting that the unwillingness of many prominent members of the Russian protest movement to drastically change the regime had already manifested itself in the winter of 2011-2012. Faced with new challenges and initially confused, the regime quickly discovered among the opposition those for whom gaining personal political capital was more important than making a real difference. Officials met with these opposition leaders (often self-appointed) and allowed their parties to register and gain admission to federal channels. This quickly did their job – the issue of dismantling of the Putin regime has disappeared from the agenda.

In contrast to Ukraine, where they recently celebrated the anniversary of the Maidan, in Russia there were no political forces ready for a radical change of the system. Nor is there such a force on the Russian political horizon today.

Putin’s dictatorship, no matter how personalistic, is not derived exclusively from Putin’s personality. The stability of this dictatorship is maintained through a system in which many influential people play a part: leaders of the “parliamentary opposition” with twenty years of experience; the chief editors of a number of respectable and respected liberal media publications; prominent “liberal” economists, who make their contribution by helping to prevent the economic collapse of the fascist regime; heads of public organizations, in charge of state grants; and many other “opponents” of the regime.

They might be genuine in their dislike of Putin, but they derive tangible benefits from the current system, and its eventual collapse carries a huge amount of uncertainty for them. That is why, when choosing between Putin and uncertainty, they have in the past, and continue today, to choose Putin.

Thus, simply stating the fact that Russia is currently ruled by a fascist dictatorship radically changes the discourse of the opposition. In particular, it becomes meaningless to continue talking about participation in the election cycle of 2016 – 2018. Every responsible opposition movement begins with the observance of certain principles, one of which is that the opposition is an alternative to the existing government, and one of its main objectives is a change of this government. In a democracy, such a change of government takes place through elections, which results in the opposition and the ruling party swapping seats, as periodically happens in all democratic countries. Under the conditions of a fascist dictatorship, change of the government through elections is impossible, and every instance of partaking in these pseudo-elections by the so-called “opposition,” only helps the regime to mask this fact.

For those who really want to put an end to the dictatorship of the Putin regime, it is time to finally acknowledge that a change of power and the radical transformation of the political system in Russia is possible only through the manner demonstrated in the Ukrainian Maidan.

Unexpectedly, the “Crimea issue” has played a catalytic role, illuminating a number of painful problems in Russian civil society and the opposition. Without solving these problems, no positive change in Russia is possible. It is time for the Russian opposition to finally grow up and realize its responsibility for the country and its future.