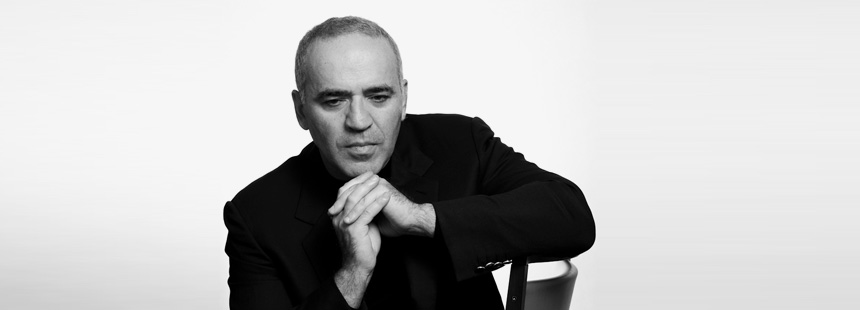

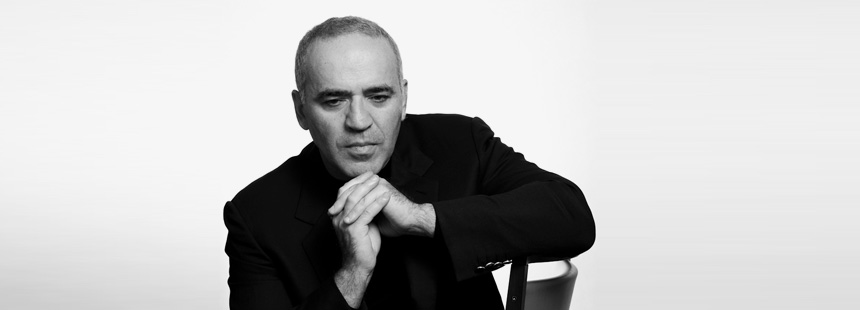

The beginning of this month marked one year since Vladimir Putin was announced as the winner of a thoroughly fraudulent presidential election, bringing him back to the Kremlin following a four-year hiatus. To mark the occasion, Garry Kasparov points out some “reforms” that the dictator has instituted over the course of his rule.

The Myth of Putin’s Successful First Term

By Garry Kasparov

March 6, 2013

It seems appropriate to take the anniversary of the return of our “national leader” to official presidential status as an opportunity to sum up some of the results of his lengthy rule.

Recently, Yekaterinburg City Duma Deputy Leonid Volkov wrote on his blog that he was sincerely surprised at how quickly “Putin’s completely psychologically normal supporters” have disappeared, and that the phenomena of “freaks for Putin” and “people for money for Putin” have replaced them. And he admitted: “I even miss them, those normal people who voted for Putin in 2000 and 2004, and didn’t have to be ashamed of their government or candidate…. But Putin’s first term is now seen as one of the most successful (if not the most successful) periods of the new history of Russia, especially from the point of view of institutional reforms.”

I was much more surprised to hear such an admission from such a forward-thinking person.

First of all, you cannot, in principle, break up the rule of a dictator who has been in power for 14 years into “terms.” That only works for democratic regimes. You can say “Obama’s first term,” or even “Yeltsin’s first term,” because at the end of his second term, Yeltsin left. But it is meaningless to say, for example, “Hitler’s first term,” when Germany began to build roads and unemployment fell, or “Stalin’s first term,” when the USSR was still undergoing NEP. History judges dictators by the totality of their actions. Everything is connected, and one period of time cannot be separated from another. Therefore, the myth of Putin’s “successful term” is no more credible than the rubbish about “the effective management of Stalin, who sometimes became overly caught up in administrative affairs.”

Secondly, Volkov’s assertion that there were successful institutional reforms in the 2000s is inherently false, although this remains a fundamental legend of the systemic liberals to this day. They tell us that important laws were passed that lower taxes, make it easier to start up a business, and so on. However, in my view, “institutional reforms” are not simply paper documents: the Duma rubber-stamps whatever decisions come down from on high. In a dictatorship, the formal content of the law is not important. What is important is how the law is applied. Reforms are only institutional if they have a noticeable effect on how people live.

Of Putin’s various early activities, he has three truly institutional reforms that immediately come to mind – ones that few “normal Putin fans” are particularly delighted with (and which a few of them are now “ashamed of their government and candidate” for):

1. NTV. The exemplary destruction of independent television. Federal media outlets have been nothing more than obedient instruments for Kremlin propaganda ever since.

2. Yukos. The exemplary destruction of a major private Russian company and the resultant seizure of its assets. Business as a whole has been held hostage as an administrative resource ever since.

3. Giving official status to Kadyrov’s criminal regime – Putin’s own way of paying tribute for a seemingly-pacified Chechnya. This model of “feudal feeding” has been spreading steadily across the North Caucasus and constituted one of the most important aspects of Russian policy ever since.

The entire legacy of Putin’s “first term” functions perfectly well on its own, but the mythical “reforms” of the systemic liberals that supposedly improved the economy do nothing to reduce brain drain, capital flight, or a level of corruption that has gone through the roof.

Translation by Kasparov.com.