Read the original article at PC Gamer

By Rich Stanton

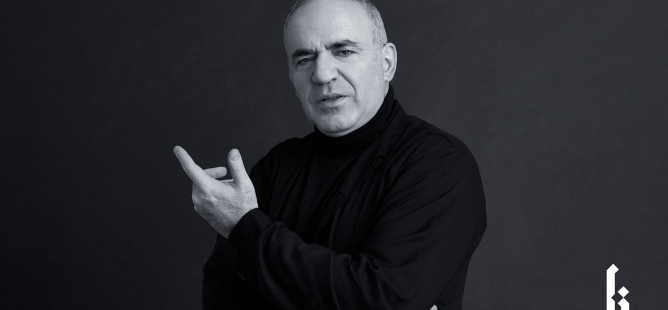

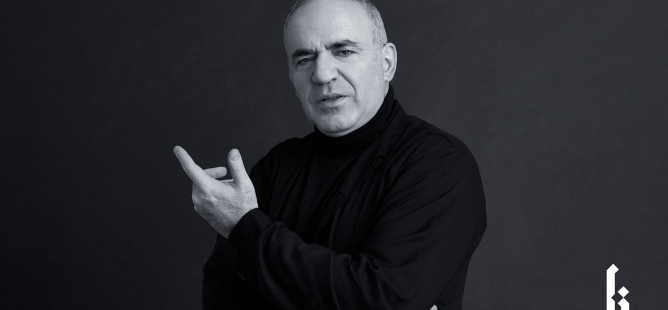

Garry Kasparov has a good case for being the best chess player in history, and not just because he’s the last world champion to have reigned before the machines took over. Kasparov himself played a major part in the latter story: as well as being involved with chess software throughout his long career, he would go on to defeat the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue in 1996 before, a year later, losing the rematch.

Kasparov played professionally from the early 1980s and became the youngest-ever world chess champion after defeating Anatoly Karpov in 1985, a title he held until a loss to Vladimir Kramnik in 2000. Kasparov played professionally until 2005 and retired as the world’s top-ranked player.

Born in Baku, Azerbaijan (then part of the Soviet Union) in 1963, the young Kasparov was taken under the wing of the legendary Mikhail Botvinnik, the first Soviet world champion. Throughout his career Kasparov has paid it on and been involved with teaching young players, and is behind various initiatives including the Kasparov Chess Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to helping educate children in the joys of the game.

The latest of these is the newly launched Kasparovchess.com, an all-encompassing chess site that includes lessons, a playing environment, documentaries, live tournaments, and a masterclass series from the man himself.

As part of the site’s launch into beta, PC Gamer was offered the opportunity to speak to the former world champion. Due to the interview’s length I’ve split our discussion into multiple articles: here we focus on Kasparov’s history with computers, and what he hopes to teach students of the game with his newest project. Check back soon for more on Deep Blue, modern machine learning, some of Kasparov’s great predecessors, and to find out if he ever played Battle Chess.

PC Gamer: Can you talk about the changes you’ve seen in the chess world over your life in regards to computers? Your career aligns with some pretty remarkable advancements. When did they start appearing as a tool for serious training? And when did it become clear they were going to become something more than that?

Garry Kasparov: A great question to start with though it may take a few hours or maybe a few days [laughs] to actually cover, you know, my career, and the influence of machines! And how the game has changed, how the game was influenced by the gradual machine takeover of many fields of the game of chess. And in some ways I can claim myself as being the last world champion, because I was the last world champion who was the strongest on this planet! [laughs] When I left professional chess, clearly the world champions were not the strongest… I don’t know, call them entities, strongest players, you know, if we take computers into account, and of course the gap keeps growing.

So today, I always say that the difference between [current world champion] Magnus Carlsen and the chess engine you can download on your laptop: it’s about the same as comparing Usain Bolt and a Ferrari [laughs] And, of course, you know, if you have a chess app on your mobile, it’s stronger than Deep Blue [the IBM supercomputer from the 1990s].

So look, it’s a natural progress. That’s not a big deal. But going back to my career, the first time I actually saw computers, real computers, that was in 1983. And it did happen in London. And I am almost sure you haven’t heard the name of the company that sponsored my semi-final match against Viktor Korchnoi: Acorn Computers! [laughs] Acorn Computers, 1983.

I was shocked because I came from the Soviet Union. That is, wow, I mean they were very primitive, absolute primitive. But you know, I was so intrigued. So I eventually asked them to give me one and I remember carrying the monitor with me in an Aeroflot flight back to Russia. So that was definitely the first computer in my town of Baku, and we played all sorts of games. You know Hopper? Remember the game Hopper?

Frogger? A frog on a road?

Yeah, exactly! Frogger with the frog! [laughs]

So in 1985, I spoke to to my new friends in Germany, the future creators of ChessBase. And I shared my idea: [it was] time to start using machines, computers to help chess players. We didn’t think about it as machines playing and chess engines, but more like a database. And I thought that could be a big help because I had all these notebooks, so how about bringing everything together? Because I could then look at these games on the screen. That’s ChessBase as created in 1986.

I had another short-term computer contract with Atari computers. You remember Atari ST? That was the beginning of the chess computer club in Moscow. I brought 53 Ataris [home] as payment for my contract [laughs] And that’s how we started first computer club in the Soviet Union.

So those are the first steps. When do computers become a tool that can help a chess world champion?

Since 1986-87 it gradually became a part of our preparation. I had a computer at home, and in 1988 I think I was the first player who bought a laptop, though I’m not sure we can call it a laptop: Compaq 486? It’s nearly five kilos and $5,000, doesn’t look like a laptop for people today, but in 1988 that was a really big deal! So I was always trying to catch up. To bring the latest technology at the time to make it part of my preparation, because I thought that would be very useful. Again: not as an engine.

The first time that I think we tried to use the engine was 1993… At the world championship match [versus Nigel Short]. Very primitive, but they still could calculate like old-fashioned calculators. And the moment that can be marked as a milestone, where a machine actually helped in preparation was 1995, my game against [challenger Viswanathan] Anand: game 10 when I checked the rook sacrifice, some of the main lines, with the machine just to make sure. Not that the machine could do much, but it could assure me that the main line was correct.

So still kind of brute-force number crunching at this point.

Exactly. But from that moment onward, machines were taking a larger and larger space in our preparation. And of course, they already could play chess because we had already many engines and Deep Blue was there. And if you look at the beginning of my career in early ’70s, where we just depended on books and magazines, and the end of my career in 2005, where books and magazines have almost disappeared as it is… it’s a different game.

Rules: rules the same. When I say different, you know, I don’t want people to get me wrong: it’s different because the preparation has its impact on the way we think, and the way we play and very few players, young players, or even experienced players, are capable of sort of building the wall between the computer screen and their eyes. The machine somehow paralyses them. It’s like a python looking at you! [laughs]

Often when we do these sessions with young players, they show the games, and they are being asked what do you think about this move or that move? They immediately give you an answer. And if I try to ask why, they stare at me like they don’t understand the question: “What do you mean why? Because the machine said so!” [laughs] Yeah, I can also look at a screen. Now, what about you? Can you just tell me in human terms, without a machine to calculate it. What do you think about the movement, why the idea is good or not good.

And also with chess today, some people suffer from this very deep preparation, because you have machines and they could do the analysis, very deep analysis, that’s 15, 20, 25 moves…

An element of surprise is gone.

So you can no longer surprise anyone. But I don’t think that we should tear out our hair or whatever’s left there or we should cry. Because it’s still a game of chess, and it still offers plenty of opportunities for creativity! Because even the machines, they need some sort of guidance if you want to get the best out of this human-machine collaboration.

So I’m not pessimistic about the future of the game. But I as I said, it’s a very different way, the way they play chess today. It’s somehow again, it’s almost like a print in your brain when you look at the board, and you just start thinking in computer geometry. There’s nothing wrong with it. But often you have to take a deep breath and just try to dissolve this connection with the computer.

What did you want to achieve with Kasparovchess?

Look, I don’t think I can say it’s going to be the best, though I’m very competitive. But I believe there’s a lot of room for development of the chess websites, and also there’s something missing that can be brought by Kasparovchess. I mean, we know that Chess24 has very strong broadcasts, it’s now bought the rights from [chess governing body] FIDE. So they’re specialising in that.

Chess.com has a good playing zone, and a lot of programs that are available. But I think it’s just what is missing that Kasparovchess could do better than our competitors is the community spirit. So that’s creating real community, global community, and also adding entertainment. So making the learning process more fun, easier to digest. And also, again, to make sure people could find this real hold there so they can build their own legacy.

It’s a general concept, but I think it’s now that the stories about the people, the great players of the past, are missing. The stories about players today, this is missing. Not so much news, more like the features section in a magazine. So I think here Kasparovchess can do better than others: we have a lot of lessons, now a lot of videos, I will be regularly involved. And again, I cannot play chess as well as Magnus [Carlsen], but I definitely can speak better than Magnus, you know, just presenting the game [laughs].

There have to be more players of chess now than ever before. Do you think we’re in the game’s golden age, and can it maintain this popularity in an age of distractions?

I heard this question many times but often in a slightly different form, with negative connotations. When people ask why chess is not as popular today, as it used to be when Fischer plays Spassky or I play Karpov, it’s simple. These people are just wrong.

It’s an optical illusion. Chess is much more popular today than 50 years ago. But it’s not just about popularity, but it’s also the size of the game of chess on the big picture. In 1972 when Fischer played Spassky the match was everywhere from television to newspaper. Because there was very little else that would compete with that. In 1985 when I beat Karpov, CNN was there already, but it was very nascent tool to promote news. And chess could steal the front page, because it was a big event.

Now today, I think the number of people playing chess, and I can tell you judging from the childrens’ competitions in the United States, it’s 1,000 times bigger than it used to be 50 years ago. But the problem is, the rest of the field grew one million times. Visually, it’s smaller because it takes a much smaller part of the big constellation of the stars, all the games, and all the other temptations and entertainments that are available through these these new devices.

But what’s happened recently, after the phenomenal success of The Queen’s Gambit, it just shows that the passion for chess is still there. Unlike other games chess has survived for what 1500 years or so. And the game always adjusted to the demands of the modern times. We live at a time where the unique values of chess have been rediscovered, so we couldn’t have a better moment to launch Kasparovchess.

You grew up in the Soviet system and a key figure for you was Mikhail Botvinnik. What were the most important things he gave you as a student and learning about the game, and what are the kind of lessons that you think are most important for students to take from you?

Botvinnik was called the patriarch of Soviet chess, the first Soviet champion, and he was a legend, you know. For me, just meeting Botvinnik in summer 1973 at age 10 [and getting an] invitation to his school, it just blew my mind. But years of hard work, and I was his favourite student, that had a great impact, because I thought it was so important to share my experience with new generations.

Botvinnik was generous. So he thought what you learned had to be given back. And when I became world champion, I started the second edition of the Botvinnik school. We had some great players, including [future world champion] Vladimir Kramnik, as our students. And ever since, I thought it was my duty to actually help younger players. And since I started Kasparov Chess Foundation in the United States in 2002, we somehow reconstructed Kasparov Academy and from 2005 to these days I’ve been working regularly with talented players, mostly in America now. We extended it to Europe and the Russian speaking universe.

But if we look at the list of players who were taught in these sessions, I think we have 16 grandmasters here. When you look at the number of young, talented players, both boys and girls, it’s very much a result of this work. And looking at the professional aspect is this: Botvinnik was known for his thorough opening preparation, and for his concentration, and, also making sure that all playing conditions, that’s all the elements of the game, that they’re being taken into account. It’s not just making the moves, but also physical preparation, making sure we are in good shape. Eating routines, there’s all these things. They had a great influence on me.

I always follow this routine. I knew no matter where I played I had to build my routine. I eat, I walk, it all had to be done almost like a machine. And my mother, she was also an engineer, she was devoted to the regime and to the strict schedule. Botvinnik’s influence was instrumental to developing some of the qualities that helped me to become World Champion.

You’re almost the anti-chess grandmaster. Because most chess world champions stay very much within the game, whereas you’ve led a very active life outside of the game, not just your interest in machine learning but involvement in politics, advocacy… what do you want to do in the future?

It’s the idea of life, you know, thanks to my mother, and somehow Botvinnik, but mainly my mother. It’s not just winning, but making the difference. So if I could use my analytical skills, my experience, my zest for life, and other qualities that I inherited from my parents, and some of them I acquired throughout my career, to make the difference. Whether it’s in chess, in education, in politics, my own country, or in any country—where I live now in Croatia—whatever I could help people to get. If it’s a better understanding of human-machine relations: I’m available!

That’s my interest. This is for the rest of my life. I will be always trying to be engaged in things where my contribution could help others.