BY

10/7/15 AT 9:44 AM

One year ago, the Russian military expanded its push into eastern Ukraine once it became clear that Europe and the United States had no interest in standing up to Vladimir Putin’s latest gambit—at least not in any way that would deter him. The core of the problem with the West’s response is that economic and political measures cannot stop a dictator’s tanks or defend a commercial airliner from a Russian missile. Putin consistently responds to words with action and he has done so again in Syria, where Russian airpower is now bolstering the murderous regime of Bashar Assad by hitting rebel forces, including those trained and supported by the United States. The Kremlin’s official pretexts, that the strikes are against ISIS and part of the global war on terror are, like most Kremlin statements, blatantly false, as can be seen by a glance at a map of Russia’s targets.

As in Ukraine, Putin will stay in Syria until it no longer suits him. He has no long-term strategic goals beyond creating chaos and weakening the alliances of the free world wherever possible. This allows him to play the big man on the international stage, an essential element of his domestic appeal. 24/7 propaganda and Soviet nostalgia have turned Putin’s invasion into a domestic hit in Russia. In contrast, Russians have no interest in Syria or Assad, but who cares what they want? Unlike the leaders of Europe, the U.S., and other democratic countries, Putin doesn’t have to worry about how popular his foreign adventures are at home. There are no checks and balances in the Russian government, no free media to criticize him, and no popularity polls that matter more than ranks of well-armed riot police.

chaos and weakening the alliances of the free world wherever possible. This allows him to play the big man on the international stage, an essential element of his domestic appeal. 24/7 propaganda and Soviet nostalgia have turned Putin’s invasion into a domestic hit in Russia. In contrast, Russians have no interest in Syria or Assad, but who cares what they want? Unlike the leaders of Europe, the U.S., and other democratic countries, Putin doesn’t have to worry about how popular his foreign adventures are at home. There are no checks and balances in the Russian government, no free media to criticize him, and no popularity polls that matter more than ranks of well-armed riot police.

This security allows dictators like Putin to move opportunistically into any breach as the White House dithers. Yesterday Ukraine, today Syria, and what about tomorrow? Africa provides inviting targets, such as Benghazi in Libya, another hot-spot where the United States has retreated. Putin is happy to sell or even make gifts of Russian weapons far and wide, especially where he smells oil.

Despite looting Russian retirement funds for cash and all his bluster about changing the world order at the United Nations last month, Putin isn’t interested in waging a big war himself. The one thing Putin’s dictatorship couldn’t stand is for its hero to look like a loser. He cannot risk a military confrontation he might lose, hence his habit of finding targets NATO isn’t willing to defend, such as Syrian rebels and Ukrainian farmers. Putin’s military pokes and prods the borders of NATO to provoke division among his opponents.

He does it in the Baltics and now he’s doing it in Turkey, a NATO member with the second-largest military in the alliance. Will America and Western Europe defend Turkish airspace or will they tell the Turks to stand down? It’s a question Putin may soon demand an answer to. Meanwhile, he’s helping Assad flood Europe with refugees while at the same time supporting anti-immigrant parties there. The cynical calculus is that when the time comes for the European Union to renew sanctions on Russia over Ukraine, perhaps a few of his allies will be in power to block them.

When I said last year that Putin was more dangerous than ISIS it was not a reference to the immense Russian nuclear arsenal, at least not directly. ISIS is dangerous and growing more so, but it is regional and would quickly be beaten down without Putin and his clients in Iran and Syria stoking civil war and creating fertile ground for ISIS’s recruiting by slaughtering Sunnis. Obama is already scurrying to avoid contact between Russian and U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq, allowing Putin to function as a nuclear-armed guarantor of Assad’s massacres.

Every Putin action that catches the West flat-footed leads to another round of what a brilliant “chess master” he is, a metaphor that annoys me more than most, as you might imagine. For years I’ve said that Putin doesn’t play geopolitical chess, and if he did he wouldn’t be very good at it. He is, however, good at playing poker with a weak hand against anxious opponents who fold against his every bluff.

The greatest danger isn’t in confronting Putin, it’s in waiting so long to do so that the stakes will be incredibly high. The longer we wait, the more confident he becomes and the more dangerous the eventual confrontation will be. Stopping Putin will be harder now than it would have been two years ago, but easier than it will be a year from now.

Putin is trapped in a downward spiral of hatred and violence. His survival at home depends on it. It will end only with a major conflict abroad and when Russians are willing to shed their blood to free themselves. When the end comes for Putin it will be the way that most dictators fall: abruptly, violently, and as a result of the economic and moral bankruptcy of the state he has created in his image.

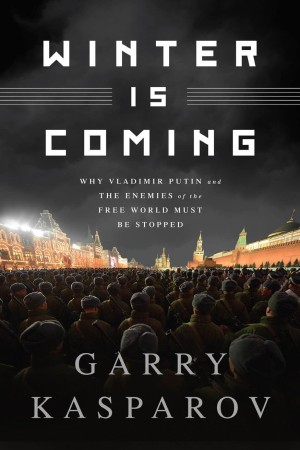

Garry Kasparov, chairman of the New York-based Human Rights Foundation, is the author of Winter Is Coming: Why Vladimir Putin and the Enemies of the Free World Must Be Stopped, out this month from Public Affairs.